The Panama Canal

In 1869 Ferdinand de Lesseps, the same man who presented the U.S. with our Statue of Liberty in 1884, celebrated the opening of "his" Suez Canal and in 1881, as president of the Panama Canal Company, he started the attempt of digging the present Panama Canal, which we traversed on Cunard's Queen Victoria on February 9.

Let us state here for all to read, this was my first "cruise" and I think for quite a few years to come, my only cruise. I had preconceived negative feelings about cruising and after this trip most of the notions have been affirmed (with the exception of meeting some lovely people), thus making me not a fan. On the other hand, when somewhere in the hopefully far future, mobility requires this means of travel, I will most likely avail myself of the lifestyle of eating, sleeping and force fed entertainment.

Returning to De Lesseps failed attempt: the French made one big mistake. And that was, that just like digging at sealevel in the dessert of Suez, they assumed they could do the same to the Ishtmus of Panama.

I will spare you the subsequent history lesson on how Teddy Roosevelt single handedly created the country of Panama, taking it forcefully from Columbia and then received as thanks the US control of the Panama Canal, which, compliments to Jimmy Carter, was returned to Panama in 1999.

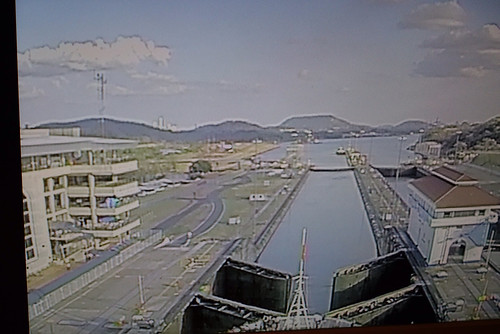

At 6 am while leaving the Caribbean Sea, we got the pilot on board at the city of Colon entering Las Minas Bay and we inched ourselves into the Gatun Locks between 7 and 7.30am. This three step lock system is actually the most impressive, bringing our ship 85 ft/26m up to the Gatun Lake, a man made lake that allows ships to travel the almost 1/3 of the way to the narrow Guillards or also named Culebra cut, the piece of continental divide rock on which the French "broke" their teeth. We ended up around 2 pm at a set of locks, named Pedro Miguel locks (a one step lock) to the Miraflores lake, lowering us to 54 ft/16.5m. About 25 minutes later we entered the Miraflores locks (a two step lock system) which would bring us down to the Pacific Ocean. About 5pm we sailed under the Bridge of the Americas into the ocean, where the pilot left us.

We had great views of Panama City while exiting the canal.

Well this was the nuts and bolts of the story. The real story is in the picture show where you can "experience" the trip best. Where you can almost hear the crunching and scratching of the hull against the lock walls, where you can see how our ship fills the lock with only yards left fore and aft.

We had great weather and saw ships ahead and behind us going through the process, a process going on 24/7 for 14,000 ships a year. The 1 millionth ship passing september 4, 2010.

This canal makes the trip of a ship going from New York to San Francisco 8,000 miles shorter (14,000 around Cape Horn, 6,000 thru the Canal)

Because more and bigger ships need to traverse this canal the new set of locks that should be opening for business in the coming year will be 180ft/55m wide instead of the present 110ft/33.5m wide and substantially longer.

I was fascinated by the statistics, and although I fear I am boring most of you to death, these few facts were sticking in my head. You must understand here that I am a numbers man. So here I go and then I let you off the hook to enjoy the pictures:

The present smaller locks hold an average 66 million gallons of lake water in their chamber, spilling per ship every time when opening their locks 52 million gallons of fresh unretrievable water into the sea. There is no pumping, it just lets Mother Nature use gravity. This means that everyday the lake supplies the equivalent of two weeks of water supply to the city of Boston to the oceans.

261 million cubic yards/200 million cubic meters of dirt and rocks needed to be excavated, an amount loaded on railroad flatcars would circle the globe 4 times. And that with the still developing technology of the 19th century/early 20th century. To say it differently you could build 63 Egyptian pyramids with it.

The new much larger locks work on new water regulating wheel gates with 3 water saving basins (don't ask me how it works) that will only require 40 percent new water per lock use, and will only have to undergo 4 hours downtime per 100,000 operating hours (that is by the way every 11.5 years)

Ok, ok, I stop here throwing statistics at you, but let it be said again: this whole Panama Canal thing is amazing and it was another must see, must do of our list.

Comments

Post a Comment